Notes Workflow

Contributed by @HardwayLinka

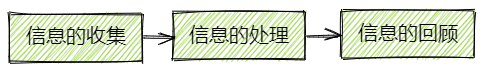

The field of computer science is vast and rapidly evolving, making lifelong learning crucial. However, our sources of knowledge in daily development and learning are complex and fragmented. We encounter extensive documentation manuals, brief blogs, and even snippets of news and public accounts on our phones that may contain interesting knowledge. Therefore, it's vital to use various tools to create a learning workflow that suits you, integrating these knowledge fragments into your personal knowledge base for easy reference and review. After two years of learning alongside work, I have developed the following learning workflow:

Core Logic

Initially, when learning new knowledge, I referred to Chinese blogs but often found bugs and gaps in my code practice. Gradually, I realized that the information I referred to might be incorrect, as the threshold for posting blogs is low and their credibility is not high. So, I started consulting some related Chinese books.

Chinese books indeed provide a comprehensive and systematic explanation of concepts. However, given the rapid evolution of computer technology and the US's leadership in CS, content in Chinese books often lags behind the latest knowledge. This led me to realize the importance of firsthand information. Some Chinese books are translations of English ones, and translation can take a year or two, causing a delay in information transmission and loss during translation. If a Chinese book is not a translation, it likely references other books, introducing biases in interpreting the original English text.

Therefore, I naturally started reading English books. The quality of English books is generally higher than that of Chinese ones. As I delved deeper into my studies, I discovered a hierarchy of information reliability: source code > official documentation > English books > English blogs > Chinese blogs. This led me to create an "Information Loss Chart":

Although firsthand information is crucial, subsequent iterations (N-th hand information) are not useless. They include the author's transformation of the source knowledge — such as logical organization (flow charts, mind maps) or personal interpretations (abstractions, analogies, extensions to other knowledge points). These transformations can help us quickly grasp and consolidate core knowledge, like using guidebooks in school. Moreover, interacting with others' interpretations during learning is important, allowing us to benefit from various perspectives. Hence, it's advisable to first choose high-quality, less distorted sources of information while also considering multiple sources for a more comprehensive and accurate understanding.

In real-life work and study, learning rarely follows a linear, deep dive into a single topic. Often, it involves other knowledge points, such as new jargon, classic papers not yet read, or unfamiliar code snippets. This requires us to think deeply and "recursively" learn, establishing connections between multiple knowledge points.

Choosing the Right Note-taking Software

The backbone of the workflow is built around the core logic of "multiple references for a single knowledge point and building connections among various points." This is similar to writing academic papers. Papers usually have footnotes explaining keywords and multiple references at the end. But our daily notes are much more casual, hence the need for a more flexible method.

I'm accustomed to jumping to related functions and implementations in an IDE. It would be great if notes could also be interlinked like code. Current "double-link note-taking software," such as Roam Research, Logseq, Notion, and Obsidian, addresses this need. I chose Obsidian for the following reasons:

- Obsidian is based locally, with fast opening speeds, and can store many e-books. My laptop, an Asus TUF Gaming FX505 with 32GB of RAM, runs Obsidian very smoothly.

- Obsidian is Markdown-based. This is an advantage because if a note-taking software uses a proprietary format, it's inconvenient for third-party extensions and opening notes with other software.

- Obsidian has a rich and active plugin ecosystem, allowing for an "all in one" effect, meaning various knowledge sources can be integrated in one place.

Information Sources

Obsidian's plugins support PDF formats, and it naturally supports Markdown. To achieve "all in one," you can convert other file formats to PDF or Markdown. This presents two questions:

- What formats are there?

- How to convert them to PDF or Markdown?

Formats

File formats depend on their display platforms. Before considering formats, let's list the sources of information I usually access:

The main categories are articles, papers, e-books, and courses, primarily including formats like web pages, PDFs, MOBI, AZW, and AZW3.

Conversion to PDF or Markdown

Online articles and courses are mostly presented as web pages. To convert web pages to Markdown, I use the clipping software "Simplified Read," which can clip articles from nearly all platforms into Markdown and import them into Obsidian.

For papers and e-books, if the format is already PDF, it's straightforward. Otherwise, I use Calibre for conversion:

Now, using Obsidian's PDF plugin and native Markdown support, I can seamlessly take notes and reference across these documents (see "Information Processing" below for details).

Managing Information Sources

For file resources like PDFs, I use local or cloud storage. For web resources, I categorize and save them in browser bookmarks or clip them into Markdown notes. However, browsers don't support mobile web bookmarking. To enable cross-platform web bookmarking, I use Cubox. With a swipe on my phone, I can save interesting web pages in one place. Although the free version limits to 100 bookmarks, it's usually sufficient and prompts me to process these pages promptly.

Moreover, many of the web pages we bookmark are not from fully-featured blog platforms like Zhihu or Juejin but personal sites without mobile apps. These can be easily overlooked in browser bookmarks, and we might miss new article notifications. Here, RSS comes into play.

RSS (Rich Site Summary) is a type of web feed that allows users to access updates to online content in a standardized format. On desktops, RSSHub Radar helps discover and generate RSS feeds, which can be subscribed to using Feedly (both have official Chrome browser plugins).

With this, the information collection process is comprehensive. But no matter how well categorized, information needs to be internalized to be useful. After collecting information, the next step is processing it — reading, understanding the semantics (especially for English sources), highlighting key sentences or paragraphs, noting queries, brainstorming related knowledge points, and writing summaries. What tools are needed for this process?

Information Processing

English Sources

For English materials, I initially used "Youdao Dictionary" for word translation, Google Translate for sentences, and "Deepl" for paragraphs. Eventually, I realized this was too slow and inefficient. Ideally, a single tool that can handle word, sentence, and paragraph translation would be optimal. After researching, I chose "Quicker" + "Saladict" for translation.

This combo allows translation outside browsers and supports words, sentences, and paragraphs, offering results from multiple translation platforms. For non-urgent word lookups, the "Collins Advanced" dictionary is helpful as it explains English words in English, providing context to aid understanding.

Multimedia Information

After processing text-based information, it's important to consider how to handle multimedia information. Specifically, I'm referring to English videos, as I don't have a habit of learning through podcasts or recordings and I rarely watch Chinese tutorials anymore. Many renowned universities offer open courses in video format. Wouldn't it be helpful if you could take notes on these videos? Have you ever thought it would be great if you could convert the content of a lecture into text, since we usually read faster than a lecturer speaks? Fortunately, the software Language Reactor can export subtitles from YouTube and Netflix videos, along with Chinese translations.

We can copy the subtitles exported by Language Reactor into Obsidian and read them as articles. Besides learning purposes, you can also use this plugin while watching YouTube videos. It displays subtitles in both English and Chinese, and you can click on unfamiliar words in the subtitles to see their definitions.

However, reading texts isn't always the most efficient way to learn about some abstract concepts. As the saying goes, "A picture is worth a thousand words." What if we could link a segment of text to corresponding images or even video operations? While browsing the Obsidian plugin marketplace, I discovered a plugin called Media Extended. This plugin allows you to add links in your notes that jump to specific times in a video, effectively connecting your notes to the video! This works well with the video subtitles mentioned earlier, where each line of subtitles corresponds to a time stamp, allowing for jumps to specific parts of the video. This means you don't have to cut specific video segments; instead, you can jump directly within the article!

Obsidian also has a powerful plugin called Annotator, which allows you to jump from notes to the corresponding section in a PDF.

Now, with Obsidian's built-in double-chain feature, we can achieve inter-note linking, and with the above plugins, we can extend these links to multimedia. This completes the process of information handling. Learning often involves both a challenging ascent and a familiar descent. So, how can we incorporate the review process into this workflow?

Information Review

Obsidian already has a plugin that connects to Anki, the renowned spaced repetition-based memory software. With this plugin, you can export segments of your notes to Anki as flashcards, each containing a link back to the original note.

Conclusion

This workflow evolved over two years of learning in my spare time. Frustration with repetitive processes led to specific needs, which were fortunately met by tools I discovered online. Don't force tools into your workflow just for the sake of satisfaction; life is short, so focus on what's truly important.

By the way, this article discusses the evolution of the workflow. If you're interested in the details of how this workflow is implemented, I recommend reading the following articles in order after this one: